Module 19 RMarkdown for creating reproducible data pre-processing protocols

The R extension package RMarkdown can be used to create documents that combine code and text in a ‘knitted’ document, and it has become a popular tool for improving the computational reproducibility and efficiency of the data analysis stage of research. This tool can also be used earlier in the research process, however, to improve reproducibility of pre-processing steps. In this module, we will provide detailed instructions on how to use RMarkdown in RStudio to create documents that combine code and text. We will show how an RMarkdown document describing a data pre-processing protocol can be used to efficiently apply the same data pre-processing steps to different sets of raw data.

Objectives. After this module, the trainee will be able to:

- Define RMarkdown and the documents it can create

- Explain how RMarkdown can be used to improve the reproducibility of research projects at the data pre-processing phase

- Create a document in RStudio using RMarkdown

- Describe more advanced features of RMarkdown and where you can find out more about them

19.1 Creating knitted documents in R

In module 18, we described what knitted documents are, as well as the advantages of using knitted documents to create data pre-processing protocols for common pre-processing tasks in your research group. We also described the key elements of creating a knitted document, regardless of the software system you are using. In this module, we will go into more detail about how you can create these documents using R and RStudio, and in module 20 we will walk through an example data pre-processing protocol created using this method. We strongly recommend that you read the previous module (module 18) before working through this one.

R has a special format for creating knitted documents called RMarkdown. In module 18, we talked about the elements of a knitted document, and later in this module we’ll walk through how they apply to RMarkdown. However, the easiest way to learn how to use RMarkdown is to try an example, so we’ll start with a very basic one. If you’d like to try it yourself, you’ll need to download R and RStudio. The RStudio IDE can be downloaded and installed as a free software, as long as you use the personal version (Posit, the company that created RStudio, creates higher-powered versions for corporate use).

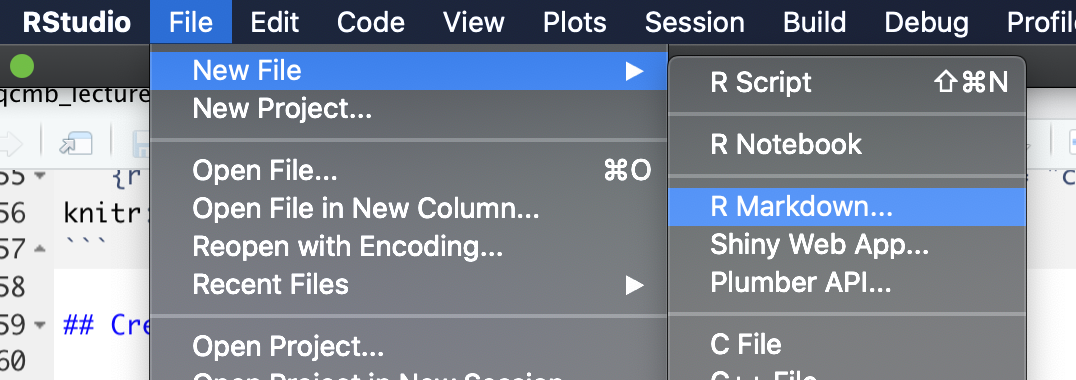

Like other plain text documents, an RMarkdown file should be edited using a text editor, rather than a word processor like Word or Google Docs. It is easiest to use the RStudio IDE as the text editor when creating and editing an R markdown document, as this IDE has incorporated some helpful functionality for working with plain text documents for RMarkdown. In RStudio, you can create a number of types of new files through the “File” menu. To create a new R markdown file, open RStudio and then choose “New File”, then choose “RMarkdown” from the choices in that menu. Figure 19.1 shows an example of what this menu option looks like.

Figure 19.1: RStudio pull-down menus to help you navigate to open a new RMarkdown file.

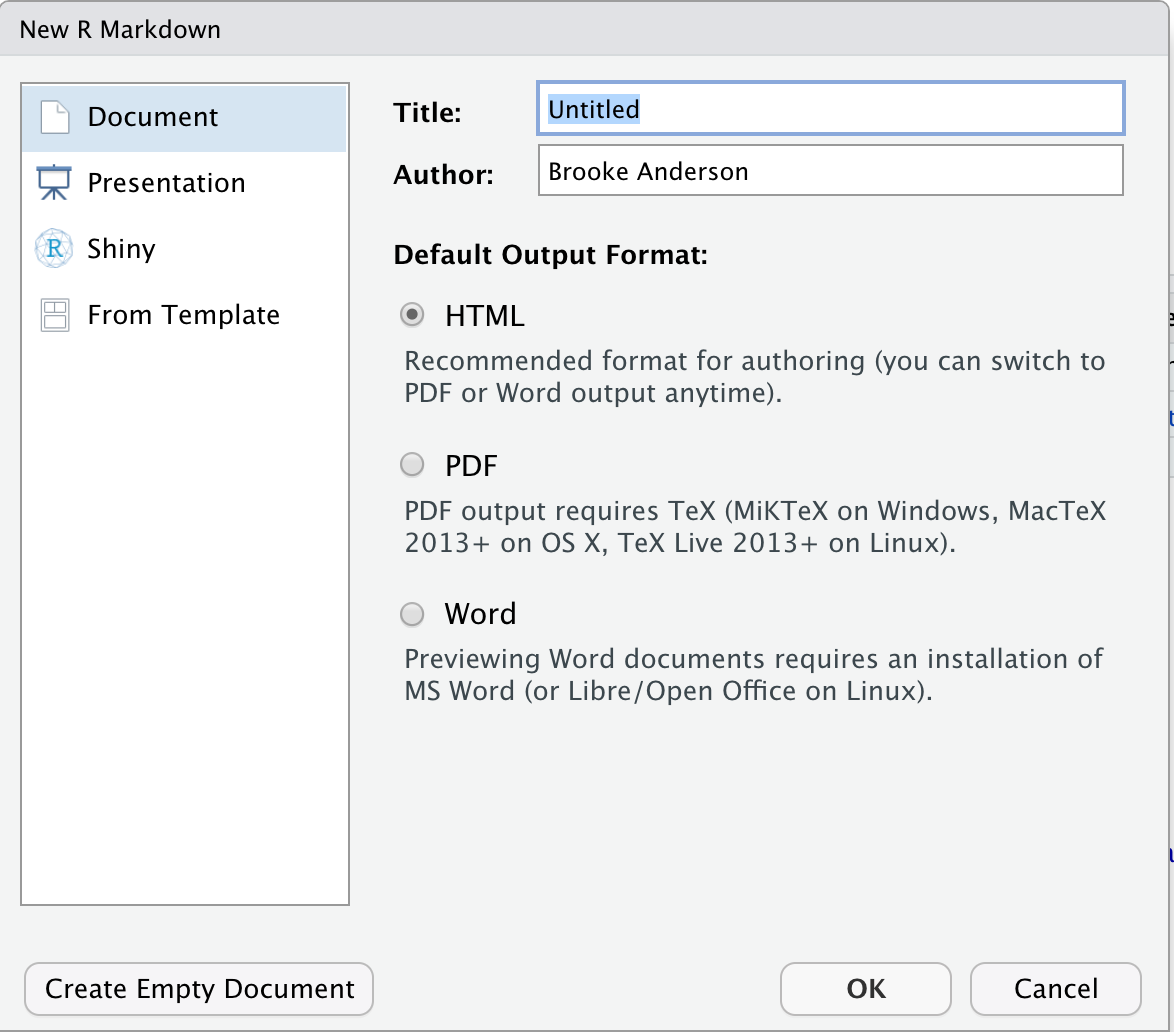

This will open a window with some options you can specify some of the overall information about the document (Figure 19.2), including the title and the author. You can specify the output format that you would like. Possible output formats include HTML, Word, and PDF. You should be able to use the HTML and Word output formats without any additional software, so we’ll start there with this example. If you would like to use the PDF output, you will need to install one other piece of software: Miktex for Windows, MacTex for Mac, or TeX Live for Linux. These are all pieces of software with an underlying TeX engine and all are open-source and free. The example in module 20 was created as a PDF using one of these tools.

Figure 19.2: Options available when you create a new RMarkdown file in RStudio. You can specify information that will go into the document’s preamble, including the title and authors and the format that the document will be output to (HTML, Word, or PDF).

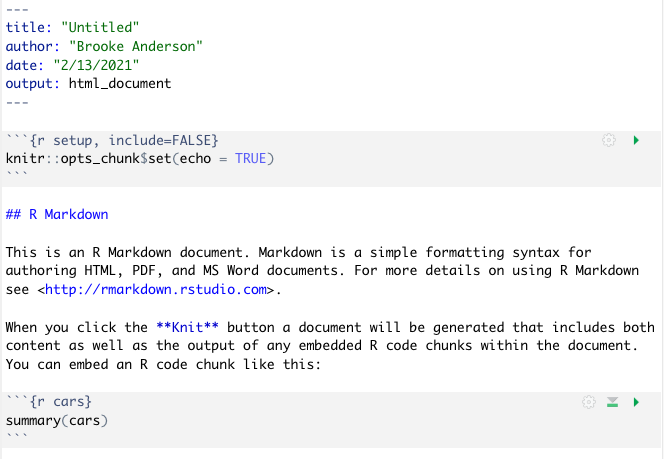

Once you have selected the options in this menu you can choose the “Okay” button (Figure 19.2). This will open a new document. This document, however, won’t be blank. Instead it will include an example document written in RMarkdown (Figure 19.3). This example document helps you navigate how the RMarkdown process works, by letting you test out a sample document. It also gives you a starting point—once you understand how the example document works, you can edit it and change it to convert it into the document you would like to create.

Figure 19.3: Example of the template RMarkdown document that you will see when you create a new RMarkdown file in RStudio. You can explore this template and try rendering (knitting) it. Once you are familiar with how this example works, you can edit the text and code to adapt it for your own document.

If you have not used RMarkdown before, it is very helpful to try knitting this example document before making changes, to explore how pieces in the document align with elements in the rendered output document. Once you are familiar with the line-up between elements in this file in the output document, you can delete parts of the example file and insert your own text and code.

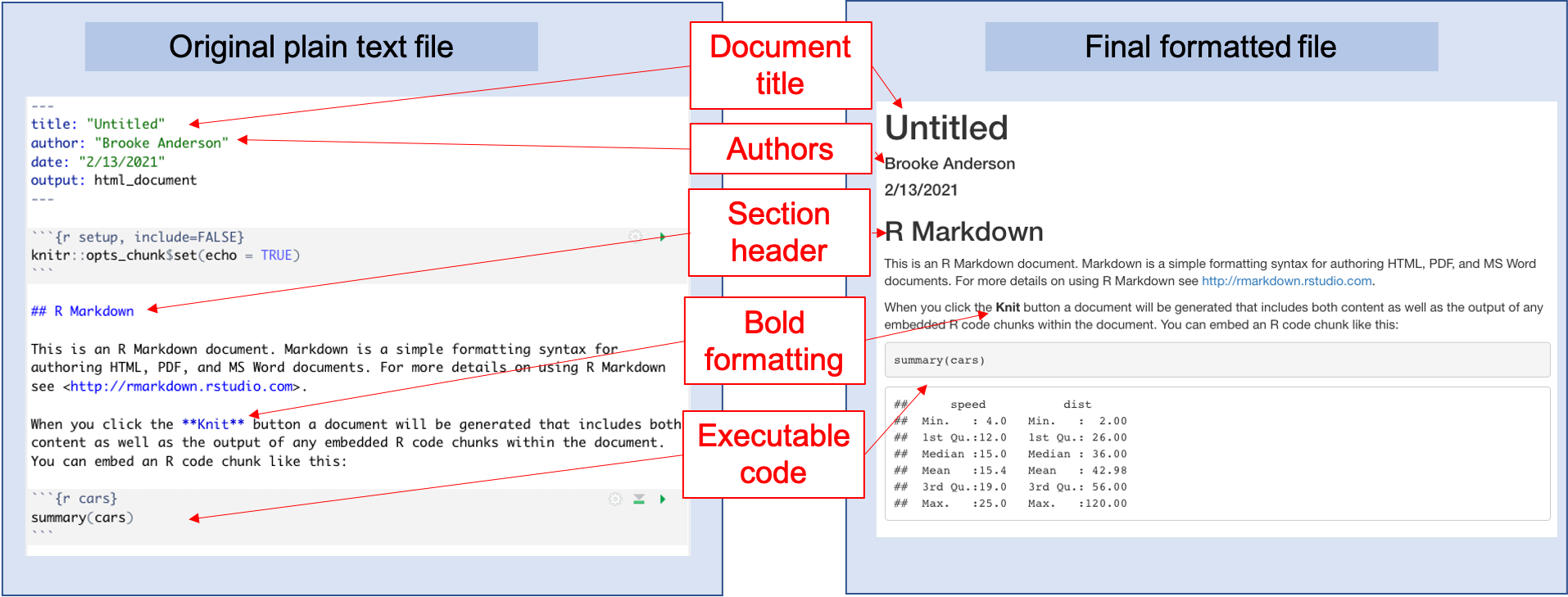

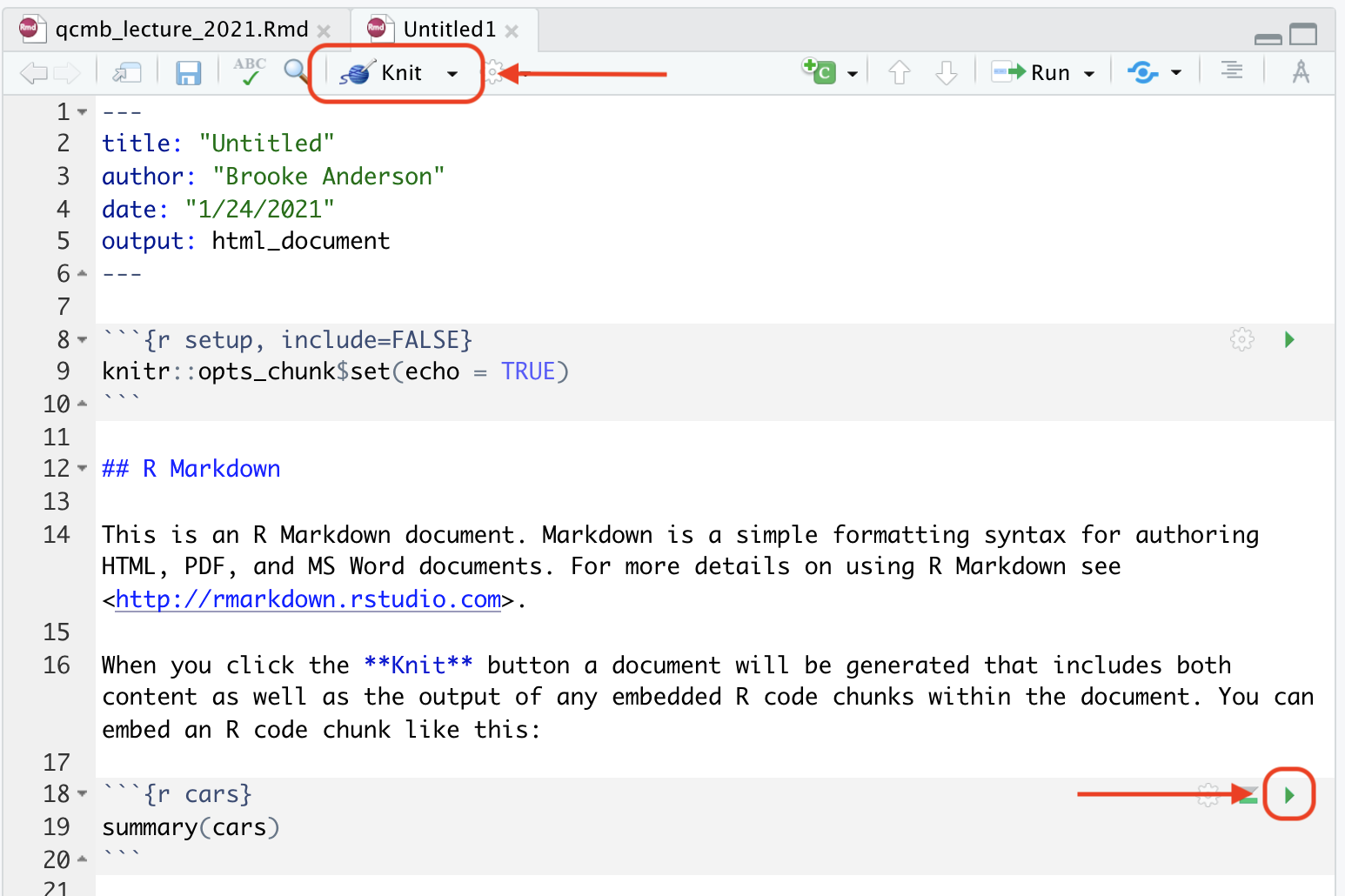

Let’s walk through and explore this example document, aligning it with the formatted output document (Figure 19.4). First, to render this or any RMarkdown document, if you are in RStudio you can use the “Knit” button at the top of the file, as shown in Figure 19.5. When you click on this button, it will render the entire document to the output format you’ve selected (HTML, PDF, or Word). This rendering process will both run the executable code and apply all formatting. The final output (Figure 19.4, right) will pop up in a new window. As you start with RMarkdown, it is useful to look at this output to see how it compares with the plain text RMarkdown file (Figure 19.4, left).

Figure 19.4: Example of the template RMarkdown document that you will see when you create a new RMarkdown file in RStudio. You can explore this template and try rendering (knitting) it. Once you are familiar with how this example works, you can edit the text and code to adapt it for your own document.

Figure 19.5: Example of the template RMarkdown document, highlighting buttons in RStudio that you can use to facilitate working with the document. The ‘knit’ button, highlighted at the top of the figure, will render the entire document. The green arrow, highlighted lower in the figure within a code chunk, can be used to run the code in that specific code chunk.

You will also notice, after you first render the document, that your working directory has a new file with this output document. For example, if you are working to create an HTML document using an RMarkdown file called “my_report.Rmd”, once you knit your RMarkdown file, you will notice a new file in your working directory called “my_report.html”. This new file is your output file, the one that you would share with colleagues as a report. You should consider this output document to be “read-only”—in other words, you can read and share this document, but you should not make any changes directly to this document, since they will be overwritten anytime you re-render the original RMarkdown document.

Next, let’s compare the example RMarkdown document (the one that is given when you first open an RMarkdown file in RStudio) with the output file that is created when you render this example document (Figure 19.4). If you look at the output document (Figure 19.4, right), you can notice how different elements align with pieces in the original RMarkdown file (Figure 19.4). For example, the output document includes a header with the text “R Markdown”. This second-level header is created by the Markdown notation in the original file of:

## R MarkdownThis header is formatted in a larger font than other text, and on a separate

line—the exact formatting is specified within the style file for the RMarkdown

document, and will be applied to all second-level headers in the document. You

can also see formatting specified through things like bold font for the word

“Knit”, through the Markdown syntax **Knit**, and a clickable link specified

through the syntax <http://rmarkdown.rstudio.com>. At the beginning of the

original document, you can see how elements like the title, author, date, and

output format are specified in the YAML. Finally, you can see that special

character combinations demarcate sections of executable code.

Let’s look a little more closely in the next part of the module at how these elements of the RMarkdown document work.

19.2 Formatting text with Markdown in RMarkdown

If you remember from module 18, one element of knitted documents is that they are written in plain text, with all the formatting specified using a markup language. For the main text in an RMarkdown document, all formatting is done using Markdown as the markup language. Markdown is a popular markup language, in part because it is a good bit simpler than other markup languages like HTML or LaTeX. This simplicity means that it is not quite as expressive as other markup languages. However, Markdown probably provides adequate formatting for at least 90% of the formatting you will typically want to do for a research report or pre-processing protocol, and by staying simpler, it is much easier to learn the Markdown syntax quickly compared to other markup languages.

As with other markup languages, Markdown uses special characters or combinations of characters to indicate formatting within the plain text of the original document. When the document is rendered, these markings are used by the software to create the formatting that you have specified in the final output document. Some example formatting symbols and conventions for Markdown include:

- to format a word or phrase in bold, surround it with two asterisks (

**) - to format a word or phrase in italics, surround it with one asterisk (

*) - to create a first-level header, put the header text on its own line, starting the line with

# - to create a second-level header, put the header text on its own line, starting the line with

## - separate paragraphs with empty lines

- use hyphens to create bulleted lists

One thing to keep in mind when using Markdown, in terms of formatting, is that

white space can be very important in specifying the formatting. For example when

you specify a new paragraph, you must leave a blank line from your previous

text. Similarly when you use a hash (#) to indicate a header, you must leave a

blank space after the hash before the word or phrase that you want to be used in

that header. To create a section header, you would write:

# Initial Data InspectionOn the other hand, if you forgot the space after the hash sign, like this:

#Initial Data Inspectionthen in your ouput document you would get this:

#Initial Data Inspection

Similarly, white space is needed to separate paragraphs. For example, this would create two paragraphs:

This is a first paragraph.

This is a second.Meanwhile this would create one:

This is a first paragraph.

This is still part of the first paragraph.The syntax of Markdown is fairly simple and can be learned quickly. For more details on this syntax, you can refer to the RMarkdown reference guide at https://rstudio.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/rmarkdown-reference.pdf. The basic formatting rules for Markdown are also covered in some more extensive resources for RMarkdown that we will point you to later in this module.

19.3 Preambles in RMarkdown documents

In module 18, we explained how knitted documents include a preamble to specify some metadata about the document, including elements like the title, authors, and output format. In R, this preamble is created using YAML. In this subsection, we provide some more details on using this YAML section in RMarkdown documents.

In an RMarkdown document, the YAML is a special section

at the top of an RMarkdown document (the original, plain text file, not the

rendered version). It is set off from the rest of the document using a special

combination of characters, using a process very similar to how executable code

is set off from other text with a special set of characters so it can be easily

identified by the software program that renders the document. For the YAML, this

combination of characters is three hyphens (---) on a line by themselves to

start the YAML section and then another three on a line by themselves to end it.

Here is an example of what the YAML might look like at the top of an RMarkdown

document:

---

title: "Laboratory report for example project"

author: "Brooke Anderson"

date: "1/12/2020"

output: word_document

---Within the YAML itself, you can specify different options for your document.

You can change simple things like the title, author, and date, but you can

also change more complex things, including how the output document is rendered.

For each thing that you want to specify, you specify it with a special

keyword for that option and then a valid choice for that keyword. The idea

is very similar to setting parameter values in a function call in R. For

example, the title: keyword is a valid one in RMarkdown YAML. It allows you

to set the words that will be printed in the title space, using title formatting,

in your output document. It can take any string of characters, so you can put in

any text for the title that you’d like, as long as you surround it with quotation

marks. The author: and date: keywords work in similar ways. The output:

keyword allows you to specify the output that the document should be rendered to.

In this case, the keyword can only take one of a few set values, including

word_document to output a Word document, pdf_document to output a pdf

document (see later in this section for some more set-up required to make that

work), and html_document to output an HTML document.

As you start using RMarkdown, you will be able to do a lot without messing with the YAML much. In fact, you can get a long way without ever changing the values in the YAML from the default values they are given when you first create an RMarkdown document. As you become more familiar with R, you may want to learn more about how the YAML works and how you can use it to customize your document—it turns out that quite a lot can be set in the YAML to do very interesting customizations in your final rendered document. The book R Markdown: The Definitive Guide,337 which is available free online, has sections discussing YAML choices for both HTML and pdf output, at https://bookdown.org/yihui/rmarkdown/html-document.html and https://bookdown.org/yihui/rmarkdown/pdf-document.html, respectively. There is also a talk that Yihui Xie, the creator of RMarkdown, gave on this topic at a past Posit conference, available at https://rstudio.com/resources/rstudioconf-2017/customizing-extending-r-markdown/.

19.4 Executable code in RMarkdown files

In module 18, we described how knitted documents use special markers to indicate where sections of executable code start and stop. In RMarkdown, the markers you will use to indicate executable code look like this:

```r{}

my_object <- c(1, 2, 3)

```In RMarkdown, the following combination indicates the start of executable code:

```{r}

while this combination indicates the end of executable code (in other words the start of regular text):

```

In the example above, we have shown the most basic

version of the markup character combination used to specify the start of

executable code (```{r}). This character combination can be expanded,

however, to include some specifications for how you want the code in the section

following it to be run, as well as how you want output to be shown. For example,

you could use the following indications to specify that the code should be run,

but the code itself should not be printed in the final document, by specifying

echo = FALSE, as well as that the created figure should be centered on the

page, by specifying fig.align = "center":

```{r echo = FALSE, fig.align = "center"}

There are numerous options that can be used to specify how the code will be run.

These specifications are called

chunk options, and you specify them in the special character combination

where you mark the start of executable code. For example, you can specify that

the code should be printed in the document, but not executed, by setting the

eval parameter to FALSE with ```{r eval = FALSE} as the marker to

start the code section.

The chunk options also include echo, which can be used to specify whether to

print the code in that code chunk when the document is rendered. For some

documents, it is useful to print out the code that is executed, where for other

documents you may not want that printed. For example, for a pre-processing

protocol, you are aiming to show yourself and others how the pre-processing was

done. In this case, it is very helpful to print out all of the code, so that

future researchers who read that protocol can clearly see each step. By

contrast, if you are using RMarkdown to create a report or an article that is

focused on the results of your analysis, it may make more sense to instead hide

the code in the final document.

As part of the code options, you can also specify whether messages and warnings created when running the code should be included in the document output, and there are number of code chunk options that specify how tables and figures rendered by the code should be shown. For more details on the possible options that can be specified for how code is evaluated within an executable chunk of code, you can refer to the RMarkdown cheat sheet available at https://rstudio.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/rmarkdown-cheatsheet.pdf

RStudio has some functionality that is useful when you are working with code in RMarkdown documents. Within each code chuck are some buttons that can be used to test out the code in that chunk of executable code. One is the green right arrow key to the right at the top of the code chunk, highlighted in Figure 19.5. This button will run all of the code in that chunk and show you the output in an output field that will open directly below the code chunk. This functionality allows you to explore the code in your document as you build it, rather than waiting until you are ready to render the entire document. The button directly to the left of that button, which looks like an upward-pointing arrow over a rectangle, will execute all code that comes before this chunk in the document. This can be very helpful in making sure that you have set up your environment to run this particular chunk of code.

19.5 More advanced RMarkdown functionality

The details and resources that we have covered so far focus on the basics of RMarkdown. You can get a lot done just with these basics. However, the RMarkdown system is very rich and allows complex functionality beyond these basics. In this subsection, we will highlight just a few of the ways RMarkdown can be used in a more advanced way. Since this topic is so broad, we will focus on elements that we have found to be particularly useful for biomedical researchers as they become more advanced RMarkdown users. For the most part, we will not go into extensive detail about how to use these more advanced features in this module, but instead point to resources where you can learn more as you are ready. If you are just learning RMarkdown, at this point it will be helpful to just know that some of these advanced features are available, so you can come back and explore them when you become familiar with the basics. However, we will provide more details for one advanced element that we find particularly useful in creating data pre-processing protocols: including bibliographical references.

19.5.1 Including bibliographical references

To include references in RMarkdown documents, you can use something called BibTeX. This is a software system that is free and open-source and works in concert with LaTeX and other markup languages. It allows you to save bibliographical information in a plain text file—following certain rules—and then reference that information in a document. In this way, it can serve the role of a bibliographical reference manager (like Endnote or Mendeley) while being free and keeping all information in plain text files, where they can easily be tracked with version control like Git. By using BibTeX with RMarkdown, you can include bibliographical references in the documents that you create, and RMarkdown will handle the creation of the references section and the numbering of the documents within your text.

To use BibTeX to add references to an RMarkdown document, you’ll need to take three steps:

- Create a plain text file with listings for each of

your references (BibTeX file). Save this file with the

extension

.bib. These listings need to follow a special format, which we’ll describe in just a minute. - In your RMarkdown document, include the filepath to this BibTeX file, so that RMarkdown will be able to find the bibliographical listings.

- In the text of the RMarkdown file, include a key and special character combination anytime you want to reference a paper. This referencing also follows a special format, which we’ll describe below.

Let’s look at each of these steps in a bit more detail. The first step is

to create a plain text file with a listing for each of the documents that

you’d like to cite. The plain text document should be saved with the file

extension .bib (for example, “mybibliography.bib”), and the listings for

each document in the file must follow specific rules.

Let’s take a look at one to explore these rules. Here’s an example of a BibTeX listing for a scientific article:

@article{fox2020,

title={Cyto-feature engineering: A pipeline for flow cytometry

analysis to uncover immune populations and associations with

disease},

author={Fox, Amy and Dutt, Taru S and Karger, Burton and Rojas,

Mauricio and Obreg{\'o}n-Henao, Andr{\'e}s and

Anderson, G Brooke and Henao-Tamayo, Marcela},

journal={Scientific Reports},

volume={10},

number={1},

pages={1--12},

year={2020}

}You can see that this listing is for an article, because it starts with the

keyword @article. BibTeX can record a number of different types of documents,

including articles, books, and websites. You start by specifying the document

type because different types of documents need to include different elements

in their listings. For example, a website should include the date when it was

last accessed, while an article typically will not.

Within the curly brackets for the listing shown above, there are key-value

pairs—elements where the type of value is given with a keyword (e.g.,

title), and then the value for that element is given after an equals sign.

For example, to specify the journal in which the article was published, this

listing has journal={Scientific Reports}. Finally, the listing has a key

that you will use to identify the listing in the main text. In this case,

the listing is given the key fox2020, which combines the first author and

publication year. You can use any keys you like for the items in the bibliography,

as long as they are different for every listing, so that the computer can

identify which bibliographical listing you are referring to when you use a key.

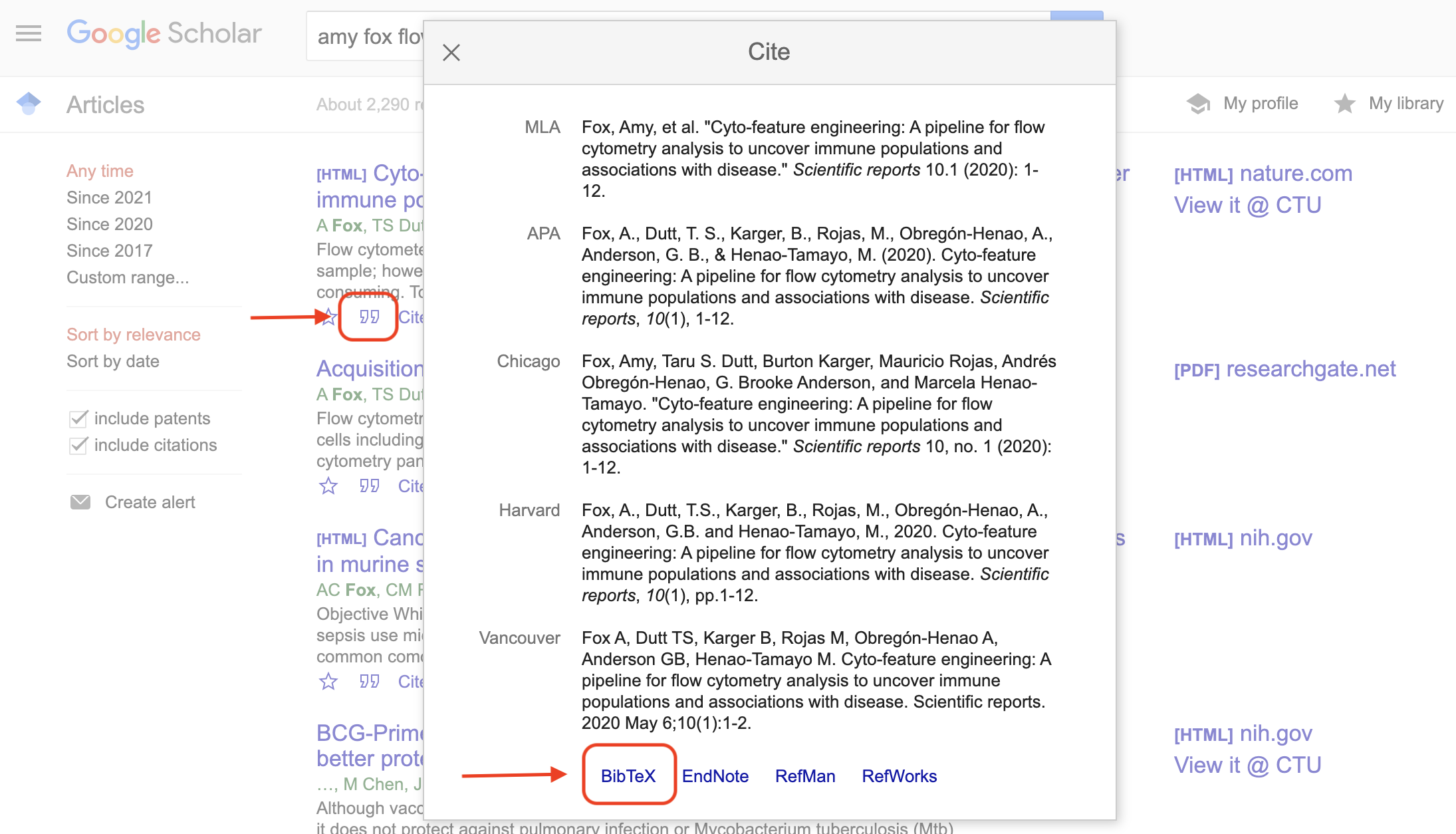

This format may seem overwhelming, but fortunately you will rarely have to create these listings by hand. Instead, you can get them directly from Google Scholar. To do this, look up the paper on Google Scholar (Figure 19.6). When you see it, look for a small quotation mark symbol at the bottom of the article listing (shown with the top red arrow in Figure 19.6). If you click on this, it will open a pop-up with the citation for the article. At the bottom of that pop-up is a link that says “BibTeX” (bottom red arrow in Figure 19.6). If you click on that, it will take you to a page that gives the full BibTex listing for that article, and you can just copy and paste this into your plain text BibTeX file.

Figure 19.6: Example of using Google Scholar to get bibliographical information for a BibTeX file. When you look up an article on Google Scholar, there is an option (the quotation mark icon under the article listing) to open a pop-up window with bibliographical information. At the bottom of this pop-up box, you can click on ‘BibTeX’ to get a plain text version of the BibTeX entry for the article. You can copy and paste this into you BibTeX file.

Once you have this plain text BibTeX file, you will tell your computer how to find it by including its path in the YAML. For example, if you created a BibTeX file called “mybibliography.tex” and saved it in the same directory as a RMarkdown document, you could use the following to indicate this file for the RMarkdown document:

---

title: "Reproducible Research with R"

author: "Brooke Anderson"

date: "1/25/2021"

output: beamer_presentation

bibliography: mybibliography.bib

---This shows the YAML for the document—the part that goes at the beginning of

the RMarkdown document and gives some metadata and overall instructions for the

document. In this example, we’ve added an extra line: bibliography: mybibliography.bib. This says that you’d like to link to a BibTeX file when

this document is rendered, as well as where to find that file (the file named

“mybibliography.bib” in the directory of the RMarkdown file).

Now that you have created the BibTeX file and told the RMarkdown file where to

find it, you can connect the two. As you write in the RMarkdown file, you can

refer to any of your BibTeX listings by using the key that you set for that

document. For example, if you wanted to reference the Fox et al. paper we

used in the example listing above, you would use the key that we set for

that listing, fox2020.

You will follow a special convention when you reference this key: you’ll use the

@ symbol directly followed by that key. Typically, you will surround

this with square brackets. Therefore, to reference the Fox et al. paper,

you’d use [@fox2021].

Here’s how that might look in practice. If you write in the RMarkdown document:

This technique follows earlier work [@fox2020].In the output from rendering that RMarkdown document you’d get:

``This technique follows earlier work (Fox et al. 2020).”

The full paper details will then be included at the end of the document, in a reference section.

19.5.2 Other advanced RMarkdown functionality

There are a number of other advanced things that you can do with RMarkdown, once

you have mastered the basics. First, you can use RMarkdown to build different

types of documents, not just reports in Word, PDF, or HTML. For example, you can

use the bookdown package to create entire online and print books using the

RMarkdown framework. This book of modules was created using this system.

You can also create websites and web dashboards, using the blogdown and

flexdashboard packages, repectively. The blogdown package allows you to

create professionally-styled websites, including blog sections where you can

include R code and results. Figure 19.7 gives an example of a

website created using blogdown—you can see the full website

here if you’d like to check out some

of the features that this framework provides. The flexdashboard package lets

you create “dashboards” with data, similar to the dashboards that many public

health departments using during the COVID-19 pandemic to share case numbers in

specific counties and states.

Figure 19.7: Example of a website created using blogdown, leveraging the RMarkdown framework.

With RMarkdown, you can also create reports that are more customized than the

default style that we explored above. First, you can create templates that add

customized styling to the document. In fact, many journals have created

journal-specific templates that you can use in RMarkdown. With these templates,

you can write up your research results in a reproducible way, using RMarkdown,

and submit the resulting document directly to the journal, in the correct

format. An example of the first page of an article created in RMarkdown using

one of these article templates is shown in Figure 19.8.338 The rticles package in R provides these templates for several

different journal families.

Figure 19.8: Example of a manuscript written in RMarkdown using a templat. This figure shows the first page of an article written for submission to PLoS Computation Biology, written in RMarkdown while using the PLoS template from the rticles package (Wendt and Anderson 2022).

RMarkdown also has some features that make it easy to run code that is

computationally expensive or code that is written in another programming

language. If code takes a long time to run, there are options in RMarkdown to

cache the results—that is, run the code once when you render the document,

and then only re-run it in later renderings if the inputs have changed. RMarkdown

does this through by saving intermediate results, as well as using a system to

remember which pieces of code depend on which earlier code. With very computationally

expensive code, it can be a big time saver, although it can also use more storage,

since it is saving more results. To include code in languages other than R, you can

change something called the engine of the code chunk. Essentially, this is the

language that your computer will use to run the code in that chunk. You can change

the engine so that certain chunks of code are run using Python, Julia, and other

languages by specifying the engine you’d like to use in the marker in the document

that indicates the start of a piece of executable code. Earlier in this module,

we showed you that executable code is normally introduced in RMarkdown with

```{r}. The r in this string is specifying that the R engine should be

used to run the code.

Finally, RMarkdown allows you to create very customized formatting, as you move into more advanced ways to use the framework. As mentioned earlier, Markdown is a fairly simple markup language. Occasionally, this simplicity means that you might not be able to create fancier formatting that you might desire. There is a method that allows you to work around this constraint in RMarkdown.

In RMarkdown documents, when you need more complex formatting, you can shift into a more complex markup language for part of the document. Markup languages like LaTeX and HTML are much more expressive than Markdown, with many more formatting choices possible. However, there is a downside—when you include formatting specified in these more complex markup languages, you will limit the output formats that you can render the document to. For example, if you include LaTeX formatting within an RMarkdown document, you must output the document to PDF, while if you include HTML, you must output to an HTML file. Conversely, if you stick with the simpler formatting available through the Markdown syntax, you can easily switch the output format for your document among several choices.

One area of customization that is particularly useful and simple to implement is

with customized tables. The Markdown syntax can create very simple tables, but

does not allow the creation of more complex tables. There is an R package called

kableExtra that allows you to create very attractive and complex tables

in RMarkdown documents.

This package leverages more of the power of underlying markup languages, rather

than the simpler Markdown language.

The

kableExtra package is extensively documented through two vignettes that come

with the package, one if the output will be in pdf

(https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/kableExtra/vignettes/awesome_table_in_pdf.pdf)

and one if it will be in HTML

(https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/kableExtra/vignettes/awesome_table_in_html.html).

19.6 Learning more about RMarkdown.

To learn more about RMarkdown, you can explore a number of excellent resources. The most comprehensive are shared by Posit, where RMarkdown’s developer and maintainer, Yihui Xie, works. These resources are all freely available online, and some are also available to buy as print books, if you prefer that format.

First, you should check out the online tutorials that are provided by Posit on RMarkdown. These are available at Posit’s RMarkdown page: https://rmarkdown.rstudio.com/. The page’s “Getting Started” section (https://rmarkdown.rstudio.com/lesson-1.html) provides a nice introduction you can work through to try out RMarkdown and practice the overview provided in the last subsection of this module. The “Articles” section (https://rmarkdown.rstudio.com/articles.html) provides a number of other documents to help you learn RMarkdown. Posit’s RMarkdown page also includes a “Gallery” (https://rmarkdown.rstudio.com/gallery.html). This resource allows you to browse through example documents, so you can get a visual idea of what you might want to create and then access the example code for a similar document. This is a great resource for exploring the variety of documents that you can create using RMarkdown.

To go more deeply into RMarkdown, there are two online books from some of the same team that are available online. The first is R Markdown: The Definitive Guide by Yihui Xie, J. J. Allaire, and Garrett Grolemund.339 This book is available free online at https://bookdown.org/yihui/rmarkdown/. It moves from basics through very advanced functionality that you can implement with RMarkdown, including several of the topics we highlight later in this subsection.

The second online book to explore from this team is R Markdown Cookbook, by Yihui Xie, Christophe Dervieux, and Emily Riederer.340 This book is available free online at https://bookdown.org/yihui/rmarkdown-cookbook/. This book is a helpful resource for dipping in to a specific section when you want to learn how to achieve a specific task. Just like a regular cookbook has recipes that you can explore and use one at a time, this book does not require a comprehensive end-to-end read, but instead provides “recipes” with advice and instructions for doing specific things. For example, if you want to figure out how to align a figure that you create in the center of the page, rather than the left, you can find a “recipe” in this book to do that.